The Broken Compass

Epistemology. What can we know? What do we think we know? I know it’s unhealthy to sit inside thinking about blog posts and piano all day; I don’t know whether $P \neq NP$, but then again I think no one does. I think His Dark Materials was a nice tv show. That’s an opinion. There are many things that you can have an opinion on. Some things that used to be known are now things you can have an opinion on; this may be an epistemological problem.

When you’re casting a ballot in an election, you need to convert a subset of your opinions into a vote. In a two-party system this seems to be easy; if you don’t know, you can always vote for the person who owns their opponent the hardest on social media. In The Netherlands we don’t have a two-party system. We have an $N$-party system, where, after elections these parties must form a government – ideally supported by a simple majority in both chambers of parliament. These parties have many opinions which they describe in platforms that are hammered out a few weeks before the elections. Collectively, these PDFs clock in at over 1.000 pages, so while reading them is clearly an option, not many people do so. Instead they watch politicians do funny things on tv, and then, a few days before the election, they go to websites where they can compare their opinions to those of the parties. The Choose Compass is one of these websites; after you answer their questions, they pencil in your political orientation on a nice map with all the parties like this one:

Something struck me as odd about this piece of political cartography. I remember my civics teacher telling us that the distinction between left- and right-wing politics was disappearing (this was ~20 years ago). Looking at this map it merely seems to have been rotated by 45$^\circ$ around whatever the $z$ axis is. This is suspicious, though. What are the odds that the entire space of possible opinions, which must be close to $\mathbb{R}^\infty$, would collapse so easily onto a line ($\mathbb{R}^1$) given the right amount of pressure exerted by a political scientist?

Another question is what these labels still mean if they’re so interchangable. If ‘leftness’ is such a strong predictor of ‘progressivism’ (and ‘rightness’ of ‘conservatism’), we might as well adopt quark-inspired naming conventions. North-west vs. south-east, Texel vs. Maastricht, sheep vs. vlaai. A fun conundrum for political scientists to figure out one day. The elections are upon us, though, so there’s probably no time for that. After the elections some of these parties will need to form a government, which the media will report on using their broken compass, which is bad because projecting on a line distorts the actual distances between parties’ ideologies.

Let’s see if we can fix this using some data from the Choose Compass.

The Choose Compass contains the positions of $N$ parties on $p$ propositions with a score ranging from ‘Completely agree’ to ‘Completely disagree.’ (They also have a ‘No opinion’ answer, but this isn’t used for any of the parties lest they come across as unopinionated.) The propositions are statements like: ‘Instead of building more homes, we should solve the housing shortage by limiting migration.’ (#15, a particularly half-baked one, since a significant fraction of these migrants come here for jobs which are either a few standard deviations above or below the average Dutch person’s station.1) Using a Javascript incantation we can scrape all the parties’ standpoints, and copypasta them into a text file.

In the Dutch system, both the number of parties and things to have an opinion on are macroscopic ($N = 16$, $p = 30$), so we’ll need to bring out some of our Big Data Tools to make sense of this. Point of departure is the opinion matrix $O$, measuring $N\times p$ entries, which, owing to the education that some of the parties we are presently discussing would like to stop funding, I’ve rescaled so that the mean and standard deviation of each column are 0 and 1, respectively. When working with so many data points it’s convenient to compress this onto a few important axes.2 We cannot plot in $p$-dimensional space, for instance, so it would be useful if we could extract the most salient features from our matrix.

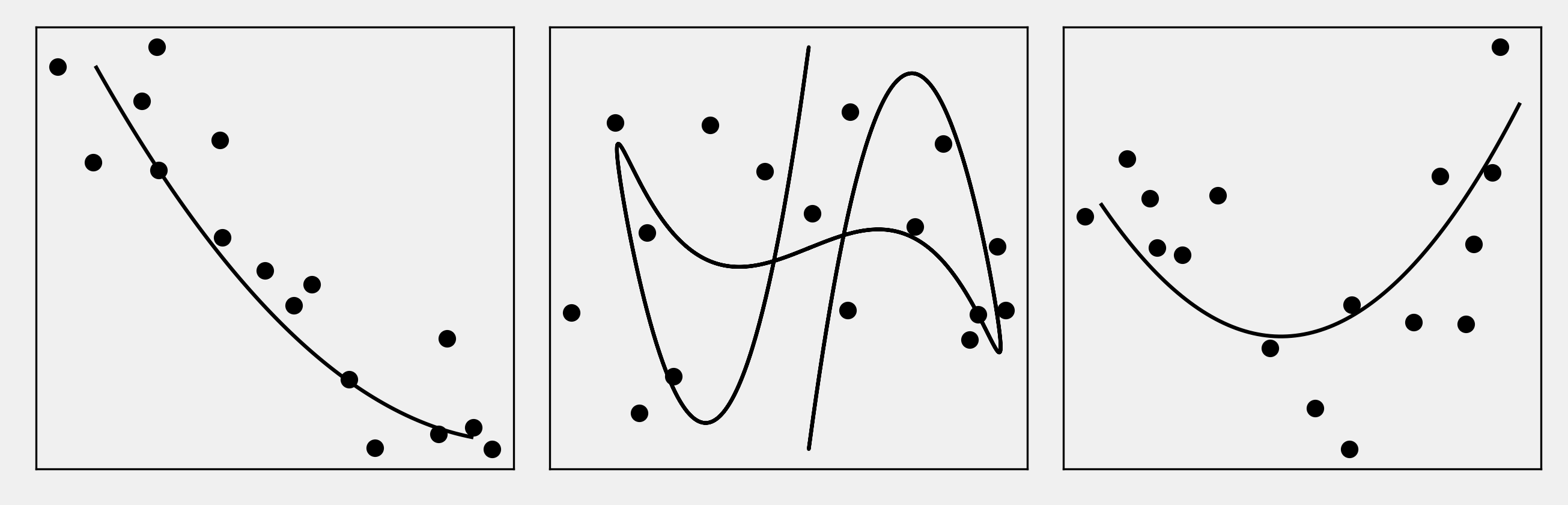

Principal component analysis3 (PCA) is an excellent tool for problems like this one. It’s the same wizardry as is used to compress the entanglement structure of quantum mechanical systems in matrix-product states, so I think it will work here, too. The goal is to project the data in our $N \times p$ matrix onto a compressed set of $p’ < p$ vectors that contain its most ‘salient’ features. PCA doesn’t tell us what these features encode, that’s up to us to figure out.

The recipe involves calculating the singular-value decomposition of $O$, which equals $O = U S V^T$. Using some math (see 3), it’s then possible to show that the columns of $V$ contain the set of ‘important’ directions in the data, while the squares of the diagonals of $S$ (which is a ‘diagonal’ $N \times p$ matrix) are their weights. Their relative values tell us to what extent a principal component explains the variance within the data (i.e. the differences between parties). When plotting these relative weights it’s pretty clear that one dominates:

I wonder what vector this first weight corresponds to? We can plot the vectors, but it’s a challenge to make sense of them. There are 30 propositions in the dataset, and labeling them on one axis becomes crowded (so please excuse my summaries). Here’s a plot showing the coefficients of the first two most significant ‘directions,’ $v_0$ and $v_1$:

Due to the normalization, the $y$ axis (agree–disagree) should be understood as relative with respect to the rest of the pack (I’ve also changed the order of the propositions for plotting reasons). Also: these vectors aren’t typical samples of parties, but it shows how their preferences correlate. Focusing on $v_0$ it’s pretty clear that this corresponds to the traditional left–right divide: “So Jesse, you’re saying you want more buses and minimum wage for all? And we should pay for that by taxing polluting companies and wealthy individuals? Are my priors correct in suggesting you are, in fact, a lefty?”

PCA doesn’t label the axes for us, so we have to do this ourselves. Let’s stick to left and right for the first component, but not proceeding without pointing out that those terms originate from where people sat in the Assemblée nationale after the French revolution. Back then they didn’t have minimum wage, let alone buses, so these should really just be considered as labels.

How important is the left–right axis? Reasonably. As per the relative weights plotted above, though, it leaves over 30% of the variance in the data unexplained, meaning these are political preferences that do not correlate with left and right.

Looking at the next vector over, $v_1$, we can observe something interesting: four propositions are dominant in determining where a party stands along this axis. They are:

- Defense spending should go to 5% of GDP by 2035.

- A copay is required to keep healthcare affordable.

- Ukraine should become a member of NATO.

- It’s best to tackle complex problems within the European Union (EU), even if that means less autonomy.

Three out of these four have to do with how parties want to position The Netherlands internationally, and the fourth is related to how they want to cough up the budget for that. Increasing the defense spending to 5% of the GDP will have a major impact on the budget, much more than spending on buses or public broadcasting, so what if we look at parties along this axis? We’ll call it the up–down axis, where up means you’re in favor of these propositions, and down means you’re against them. By taking the inner product of $v_0$ and $v_1$ with the parties’ positions, we can project each party on our two axes, which results in this new map of the political landscape:

A coalition is typically formed by parties that are close to one another by some metric, so how should we think about the distance between parties in this territory? On the old map, SP (Socialist Party) and DENK (Think) were pretty close to D66 (Democrats ‘66) because they have similar ideas of the extent to which the government should support people. They are significantly further apart, however, on the up–down axis. This makes sense, because 5% of the GDP that’s spent on defense cannot go to healthcare or to extending the minimum wage to more people.

Now, in closing, here’s an opinion: I think it’s inane that tv channels have hosted hours of debates that did not address this major realignment in government spending. Here’s some facts: 5% of the Dutch GDP is 50 billion €, which is 2.5 times the 20 billion € that’s currently spent on defense on a yearly basis. Instead, these debates honed in on the ‘question’ of why all the migrants get to live in subsidized housing. The yearly housing budget is roughly 7 billion € (which includes everything: from social housing to home ownership subsidies). With the additional defense spending, the government could fund its housing efforts four times over. I think increasing our defense spending is important, but I wonder whether, given the choice, everyone else would agree. Looking at the parties, at least, there’s some variance in their thinking on this, and I imagine this reflects the general population. If anything, it would be at least more interesting to go beyond the left–right divide, and to have a debate on our role in the world and how we plan to afford it, rather than the discriminatory ‘question’ of whether the constitution should grant the same rights to Muslims as it does to Christians.

Data & analysis

I’ve uploaded the notebook that I’ve used for the analysis and for generating the figures. For posteriority, you can also find the data of the Choose Compass and the list of propositions here.

Notes

-

Corollary: We should solve the housing shortage by increasing the variance of the education level of the Dutch population. Conundrum: Do we accomplish this by spending more or less on education? ↩

-

This is exactly what the Choose Compass has done in their figure, but because they’ve stuck to a progressive–conservative axis, the additional dimension can be considered redundant. ↩

-

A high-bias, low-variance introduction to Machine Learning for physicists, Mehta et al., Physics Reports 810, 2019, 1–124 ↩ ↩2